Atelier: un.Sichtbare ver.Hinderung – Change of perspective and performance (2019)

The atelier “un.Sichtbare ver.Hinderung” was informed by the principle of the UN Commission on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities of 2006, which was ratified in Switzerland in 2014 and followed the motto “Not without us above us”. The echo group atelier “un.Sichtbare ver.Hinderung” was conceived, prepared and realized with this understanding in close collaboration with Herbert Bichsel, Nicole Pfister and Edwin Ramirez.

The basic structure of the sequences of the atelier was experience-based. The aim was to open up new horizons of thought and action through theoretical discussion and reflection on subjective experience.

Experiencing and walking: CHANGE OF PERSPECTIVE

The meeting point for this sequence was in front of the railway station in Brugg-Windisch. Here, the first “obstructions” in public space could be experienced directly. After a brief welcome by the core team, the two experts Herbert Bichsel and Nicole Pfister introduced the first sequence. The “change of perspective” developed by the organization Sensability allowed the experience of three contexts of perception:

Firstly, the “experience“ and “inspection“ of the Brugg-Windisch campus in wheelchairs or with dark glasses made it possible to perceive various access barriers. This allowed a next step: the participants were made aware of their own helplessness in relation to these previously unnoticed (or barely noticeable) obstacles that prevent access to public spaces. Finally, the sensory experience made it possible to become aware of one’s own body in a new way and to make more conscious use of our sensory system.

Informal exchange of experiences: MURMURING

Upon entering the work space designed for this atelier, the participants were given the opportunity to engage in informal exchanges sharing differing insights experienced during the previous sequence “change of perspective”. They then were invited to take a seat in the theater stage installed in the studio space.

The ambiguity of humor: PERFORMANCE

On this stage, Edwin Ramirez (see photo below) opened up another change of perspective with his performance. By performing situations related to his everyday experiences on stage, he addressed, among other things, the inability of his fellow human beings to meet him without prejudice, without hindering him, and invited us to laugh with and at our own awkwardness. Edwin describes humor as a personal survival strategy: For him, it is a way of breaking down fears of contact with people with disabilities and of opening up opportunities for real encounters. Laughter also became a matter of potentialities in the context of the atelier, allowing new negotiating possibilities.

The ambiguity of the situations performed by Edwin Ramirez became palpable in the laughter: At a superficial level, a situation comedy that makes one laugh with relief, but at the same time the exposure of a second, initially invisible level that makes the laughter getr stuck in one’s throat. In Edwin’s words, he does not make “disabilty jokes”, but tells seemingly funny stories from a first-person perspective, which on closer inspection appear bizarre or violent. For him, humor becomes a form of aesthetic appropriation of the self and the world.

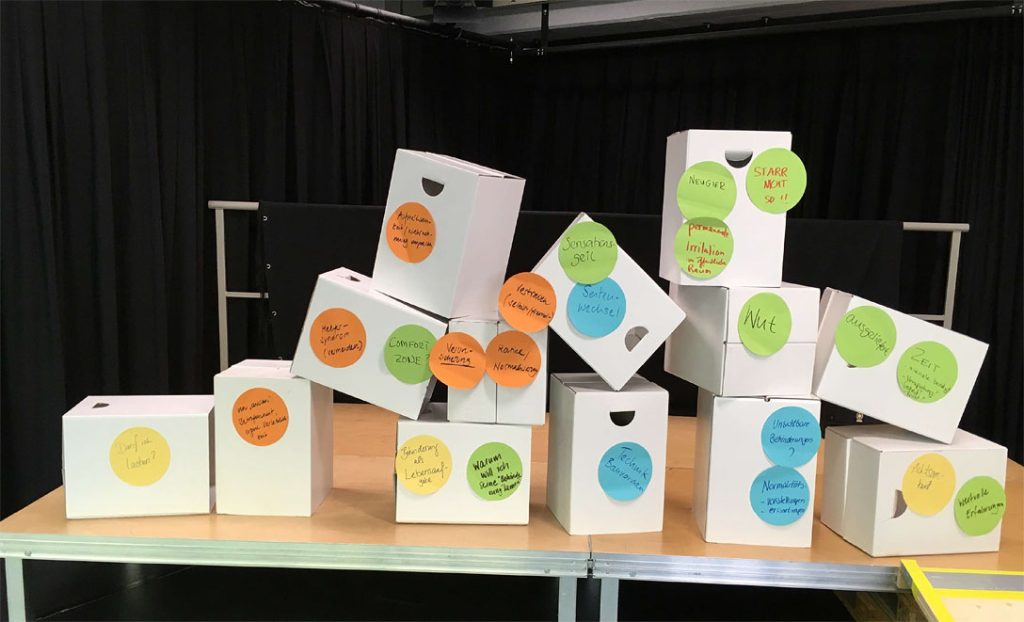

In a nutshell: CONCEPT BOXES

In three groups, the participants reflected on what they had experienced, how they found their way into an obstacle and the ambiguity of the performance.

The groups were given three questions as way of orientation for considering change of perspective:

- What uncertainties, irritations, resistances do we encounter when trying to change our perspective?

- What (un)knowledge becomes visible?

- What possibilities and impossibilities can occur?

The first brainstorming session took place separately: among the participants and among the experts with practical experience. These separate settings were intended to enable the “chronically multiple normals” to have an “unbiased” exchange in which they could become aware of their apparent normality and spontaneously express their discomfort and ignorance. In a second step, the experts joined the groups of participants. Together, they looked for ways to deal with the lack of knowledge and to develop a nuanced language for the inability and the different positions and to develop new options for action for working together.

The diverse ideas, concepts, topics and new words were pinned onto “concept boxes” and piled up to form a sculpture of newly moving knowledge. The boxes had already been introduced in a previous atelier as so-called “stumbling blocks”. Surrounded by these sculptures, they reflected concepts, topics and words that cause us to stumble, over which we have “stumbled” and which need to be addressed.

Finally, the focus lights turned back to the experts. True to the motto “Not without us about us”, their observations of the previous sequences and their explanations became a mirroring device and thus a central corrective for emergence of new knowledge: Edwin Ramirez emphasized that it can be an important experience to feel uncertainty. Dialogue is central to dealing with this uncertainty, but it also requires a new temporality or time structure, which is referred to as “crip-time” in disablity studies.

Nicole Pfister called for greater mindfulness in disabling situations, in the sense of being aware of current events and experiences, and problematized the double burden of not only being disabled oneself, but also having to think for “chronically multiple normals” (e.g. having to avoid persons with cellphones on railway platforms).

Herbert Bichsel addressed the contradictory nature of the helper syndrome. All too often, “helpers“ objectify the other subject, deny them independence, overlook structures of obstruction and incapacitate them. The perception of the person as an independent subject is central; as a person who is hindered in concrete situations and by concrete structures.

From the current situation to “must become” situation

Herbert Bichsel opened the subsequent discussion sequence with a historical reconstruction of the social legal situation for people with disabilities. With this contextualization, he made it possible to locate the situation in terms of time and content from the beginnings of the disability movement to the ratification of the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities at the UN General Assembly in New York in 2006. With the adoption of the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, the United Nations took a remarkable reform step in terms of international law and disability policy, which aims to remove the numerous attitudinal and social barriers that continue to severely impair the autonomous lifestyle and barrier-free participation of people with disabilities in all areas of society and thus constitute a violation of human rights.

Article 24 of the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities is relevant with regard to discrimination structures in the education system. It emphasizes the right of people with disabilities to education. Based on the principle of equal rights, the signatory states undertake to ensure the full participation of all people at all levels of the education system. Within the education system, appropriate provisions must be made and suitable measures introduced to ensure equal access to general higher education, vocational training, adult education and lifelong learning in addition to basic education. Article 24.5 of the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities in particular stands for this right:

“States Parties shall ensure that persons with disabilities have access, without discrimination and on an equal basis with others, to general higher education, vocational training, adult education and lifelong learning. To this end, States Parties shall ensure that reasonable accommodation is made for persons with disabilities.” (Art. 24.5)

Current situation

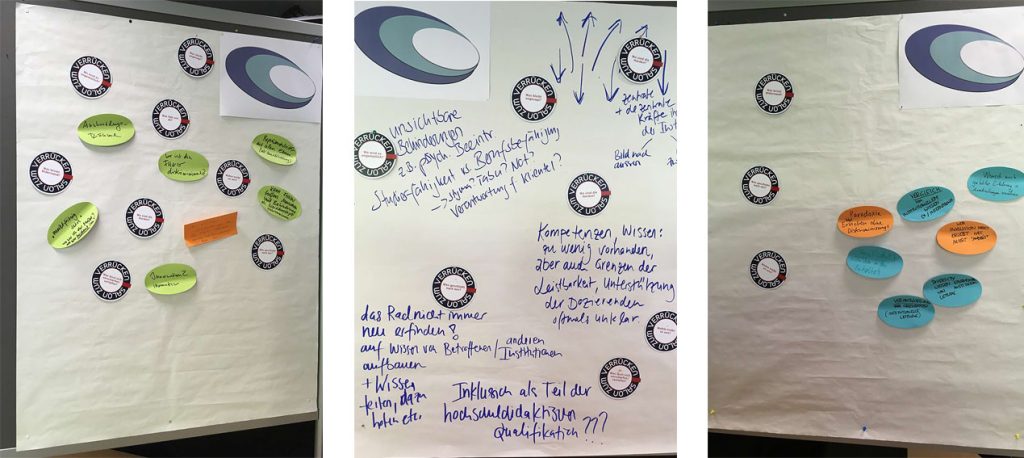

Subsequently, the question of the conditions that prevent the full participation of people with disabilities at the FHNW was raised. In a moderated discussion between Herbert Bichsel (Equal Opportunities Officer of agile.ch) and Natalie Berger (Coordinator Diversity and Sustainability FHNW), the various levels of the university context were examined:

- Level 1: Where do we stand in terms of accessibility to higher education? (Who has access to our universities? Are there differences at the individual sub-universities? Are there differences for students, lecturers and staff?)

- Level 2: Where do we stand in terms of accessibility at the university? (What accessibility does the educational institution guarantee? Are there differences at the individual sub-universities? Are there differences for students, lecturers, employees?)

- Level 3: Where do we stand in terms of inclusive university teaching? (How does the university organize barrier-free teaching and learning, alternative forms of examination, technical aids, writing assistance, etc.? In which degree programs are issues of disability/absenteeism actually included and not simply treated as an “add-on“? To what extent are teaching/learning situations designed to be accessible?

Two key aspects were made clear in the discussion. Firstly, it became clear that accessibility to the university must be considered far beyond structural measures. The agreement on standards for elevators, doors and ramps is usually only the lowest common denominator that development groups finally agree on. In order to bring about real change, a cultural change is needed within the organization and its communication processes, as well as a welcoming culture. This does not only apply to students, but also to staff, lecturers and professors.

Secondly, the tension between individual solutions and uniform collective processes was pointed out. It became clear that a cultural change is moving in this area of tension: on the one hand, there should be fundamental concepts at a general level and, at the same time, always the possibility of developing individual solutions in the short term. According to Herbert Bichsel, it is important to work on both levels true to the motto “Not without us about us”: not only to ask those affected what they need, but also to involve them as experts in change processes from the outset.

“Must become” situation

In the knowledge of the possibilities already realized and not yet realized, the question is raised as to what could and should be possible at the FHNW and its sub-universities.

Together in small groups, the participants now have the opportunity – based on their own examples and a discussion of the status quo – to imagine various future perspectives. In the discussion at the three levels of the university context, individual possibilities for implementing the needs horizon will also be addressed.

Some results of the discussion:

- Inclusion as a higher education didactic premise of all courses

- Focus not exclusively on students, there is also a need for development in the area of staff , understanding the university as a place of work

- further open access to research

- Remove the taboos surrounding invisible disabilities, e.g. mental impairments

- Build on the knowledge of those affected, with those affected as experts

- Reformulate job advertisements

Meta-reflection and outlook

Finally, the experience was placed on a third level in the overall project context. The internal views of the “un.Sichtbare ver.Hinderungen” atelier show once again that the development of diversity-oriented and heterogeneity-sensitive university teaching requires work on the conditions and circumstances under which university teaching takes place at the FHNW. It would be short-sighted to understand continuing education in this area only as an individual qualification measure. Continuing education requires time and resources in order to open up spaces for negotiation and imagination that enable critical diversity literacy at all levels of the higher education context and among all participants.

The constellation of experience-based workshops has shown that a committed movement of reflection with an increasing number of participants, who also act as multipliers for their sub-universities, can lead to groundbreaking insights and new possibilities for social action. Against this background, the central question of this meta-reflection was: What kind of continuing education settings should be specifically constellated and rendered accessible in a continuous ways addressing various concerns and needs of the sub-universities?

Some highlights:

- A performative approach would be well suited for further education offers in universities of art and design.

- The concrete experience of changing perspectives and the humorous-performative approach is an excellent starting point for learning to perceive obstacles and to question one’s own patterns of thought and perception.

- The need to embed diversity in the content of the disciplines, e.g. in terms of topic, specialist cultures and language

- The playful approach of changing perspectives and comedy is refreshing. This also helps to break the prevalent mode of communication “I’ll come and show you how to do it right because you’re doing it wrong”.

- Disability is a suitable topic for opening doors, as it is an issue that potentially affects us all and at the same time (in contrast to the category of race, for example) is not perceived from the outset as a threatening political issue.

Edwin Ramirez and Herbert Bichsel concluded the discussion. Both felt that the echo group meeting was positive, with many useful ideas, but at the same time they pointed out that the strong and ongoing commitment must be translated into everyday life, as there is still a lot of work ahead of us.